Full Text Article Open

Access

Case

report

Non-bacterial

osteitis: Chronic Recurrent Multifocal Osteomyelitis

or pediatric SAPHO?

Triki

Ramy1,2,*,Daoudi Samih1,2,Guermazi

Bassem1,2,Kamoun Khaled1,2,Jlalia Zied1,2**,Jenzri Mourad1,2.

|

1: Department

of Pediatric Orthopedics Kassab

Institute, Ksar Said 2: College

of Medicine University

of Tunis El Manar Tunis

Tunisia * Corresponding

author ** Academic

Editor Correspondence

to: Trikiramy0816@gmail.com Publication

Data: Submitted:

March 5,2020 Accepted:

May19,2020 Online:

June 30,2020 This article was subject to full peer-review. This is

an open access article distributed under

the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution

Non-Commercial License 4.0 (CCBY-NC)

allowing sharing and adapting. Share:

copy and redistribute the material in any medium

or format. Adapt:

remix, transform, and build upon the

licensed material. the work

provided must be properly cited and cannot be used for commercial purpose. |

Abstract |

|

Chronic

Recurrent Multifocal Osteomyelitis (CRMO) and SAPHO syndrome represent the

group of autoinflammatory bone disease responsible

for recurrent non-bacterial osteitis (NBO). both are considered as defects of innate immunity. The

most common clinical presentation is recurrent episodes of bone pain with or

without fever.The clinical and imaging features are

non-specific.This usually leads to late and

confusing diagnosis. We

hereby report a case of CRMO in a 12-year-old patient. The aim is to

highlight the confusing overlap of clinical features between CRMO and SAPHO

syndromes. Keywords: multifocal osteomyelitis,

non-bacterial osteitis, SAPHO, bone pain. |

|

|

Observation A

12-year-old female patient with a history of recurrent metatarsalgia in the past year

presented with right thigh pain of three weeks duration. The pain was related

to exertion in the beginning and became permanent later. A fever of three

days duration preceded the onset of the pain. The examination revealed a

small painful swelling in the right thigh. Joint and skin examinations were

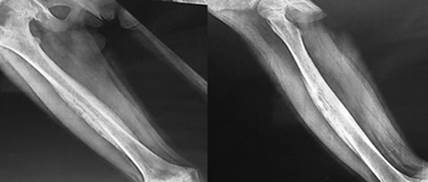

normal. X-rays

of right femur showed multilamellar inflammatory

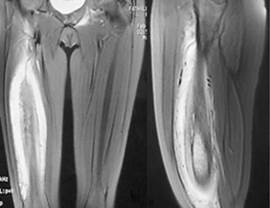

reaction of the shaft (Figure1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed

heterogeneous mass withT1 hyposignal and T2 hypersignal which was diffusely infiltrating the muscles

(Figure 2). The

abdominal ultrasound and chest CT scan were normal. Laboratory exams revealed

high CRP and ESR. The hemoglobin rate was normal. The X-rays of both feet

showed multilamellar reaction of the 2nd

and 4th left metatarsal, bones and also of the right 2nd

metatarsal bone(Figure 3). MRI of the whole body

showed multiple lesions in the proximal and distal metaphysis of the left humerus, right humeral shaft, left acetabulum, pubic

rami, the right side of the sacrum and the right femoral neck (Figure 4).

Bone biopsies were performed from the femoral mass to rule out Ewing’s

sarcoma. Histopathology

examination showed non-specific chronic inflammatory cell reaction and

fibrosis. There was no sign of malignancy and the culture was sterile. Majeed syndrome was considered as differential but not

retained due to the absence of anemia and similar familial history. The

patient was treated by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and showed good

response. At 2-months follow-up there were satisfactory biological and

radiological improvements. |

|

Figure1 |

|

|

Figure 2 |

Figure 3 |

|

Figure 4 |

Figure

1: X-ray of the femur showing multilamellar

reaction Figure

2: MRI aspect of infiltrating right thigh mass Figure

3: X-rays of both feet

showing multiple metatarsal inflammatory processes. Figure

4: cartography of the different CRMO sites. |

Discussion

Typically,

CRMO presents as recurrent bone pain with or without low grade fever [1]. Episodic

exacerbations and remissions are characteristic. The bone pain has usually

insidious onset. Objective signs of arthritis may involve one or more joints

[2]. The skin findings include psoriasis, palmoplantar

pustulosis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and cystic scarring acne. The average age of

onset is 10 years (4-55years). Bone involvement in CRMO has usually an

asymmetric distribution with predilection for long bones of lower extremities.

This can mimic infectious

osteomyelitis or malignant tumors in children. During exacerbations, high CRP and ESR are

found in more than half patients. However, it is not usual to find objective

anemia and Rheumatoid factor is negative. Only ten percent of patients are

positive for HLA-B27[3]. Comorbid conditions

found in CRMO may include spondyloarthropathy, psoriatic arthritis

as well as Inflammatory Bowel Disease (Crohn’s

disease or ulcerative colitis). Comorbid conditions can be absent in the onset

of the disease and

appear after 1 to 5 years of evolution[4,5].

SAPHO

is also characterized by episodic recurrent bone pain due to non-bacterial osteitis [6]. The most commonly affected bones are located

in the chest wall [7]. The osteitis can be unifocal or multifocal and

asymmetric. One of the distinguishing SAPHO features is the finding of severe

skin manifestations. Severe scarring acne, psoriasis or palmoplantar

pustulosis are commonly present on examination. SAPHO

syndrome has an older age of

presentation. The onset is usually at 30 years(12-65

years) [6,7]. Moreover, SAPHO has predilection for different bones.

In

our case most of the lesions were located in long bones and the chest wall was

free. The diagnosis of CRMO was more plausible.

In

all cases, both CRMO and SAPHO should be diagnosis of exclusion. It is always

mandatory to rule out infection, malignancy, and systemic autoimmune diseases. The

diagnosis is usually made on both clinical and radiological arguments. The MRI

whole body could be useful. It detects infra-clinic osteitis

sites. The cartography of the lesions could evoke the diagnosis [8]. The

treatment is almost always based non-steroidal anti-inflammatory molecules for

mild cases. Otherwise corticosteroids and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist

(IL-1Ra) may be required. The indications for surgery are rare [9,10].

Conflict

of Interest: None

Acknowledgments

We

thank Professor Mouna Bouaziz-Cheli

and Professor Noureddine Bouzouaya

for collaborating in the management of this patient.

This

report does not contain any personal information that could lead to the

identification of the patient. A parent’s consent was obtained.

References

[1]

Hofmann SR, Kapplusch F, Girschick

HJ, Morbach H, Pablik J,Ferguson PJ et al.

Chronic Recurrent Multifocal Osteomyelitis (CRMO): Presentation, Pathogenesis,

and Treatment. Curr Osteoporos

Rep. 2017;15:542-54.

[2]

Roderick MR, Shah R, Rogers V, Finn A, Ramanan AV.

Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) - advancing

the diagnosis. Pediatr Rheumatol

Online J. 2016;14:47.

[3]

Hofmann SR, Kubasch AS, Range U, Laass MW

, Morbach H , Girschick HJ,

et al. Serum biomarkers for the diagnosis and monitoring of chronic recurrent

multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO). Rheumatol Int. 2016;36:769-79.

[4]

Jelušić M, Čekada

N, Frković M, Potočki

K, Skerlev M, Murat-Sušić

S, et al. Chronic Recurrent Multifocal Osteomyelitis (CRMO) and Synovitis Acne Pustulosis

Hyperostosis Osteitis (SAPHO) Syndrome - Two

Presentations of the Same Disease? Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2018;26:212-19.

[5]

Yamashita

K, Calderaro C, Labianca L,

Gajaseni P, Weinstein SL.

Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) involving spine: A case

report and literature review. J Orthop Sci. 2018;S0949-2658(18)30168-4.

[6]

Firinu D, Garcia-Larsen V, Manconi PE, Del Giacco SR. SAPHO

Syndrome: Current Developments and Approaches to Clinical Treatment. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2016;18:35. [7] Cianci F, Zoli A, Gremese E, Ferraccioli G. Clinical heterogeneity of SAPHO syndrome:

challenging diagnose and treatment. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36:2151-58.

[8]

Jurik AG, Klicman RF, Simoni P, Robinson P, Teh J.

SAPHO and CRMO: The Value of Imaging. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol.

2018;22:207-24.

[9] Daoussis D, Konstantopoulou G, Kraniotis

P, Sakkas L, Liossis SN. Biologics

in SAPHO syndrome: A systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;48:618-25.

[10]

Vargas

Pérez M, Sevilla Pérez B. SAPHO syndrome in

childhood. A case report. Reumatol

Clin. 2018;14:109-112.